Barycentric coordinates (astronomy)

In astronomy, barycentric coordinates are non-rotating coordinates with origin at the center of mass of two or more bodies.

The barycenter (or barycentre; from the Greek βαρύκεντρον) is the point between two objects where they balance each other. For example, it is the center of mass where two or more celestial bodies orbit each other. When a moon orbits a planet, or a planet orbits a star, both bodies are actually orbiting around a point that is not at the center of the the primary (the larger body). For example, the moon does not orbit the exact center of the Earth, but a point on a line between the center of the Earth and the Moon, approximately 1,710 km below the surface of the Earth, where their respective masses balance. This is the point about which the Earth and Moon orbit as they travel around the Sun.

Contents |

Two-body problem

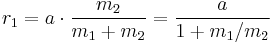

The barycenter is one of the foci of the elliptical orbit of each body. This is an important concept in the fields of astronomy, astrophysics, and the like (see two-body problem). In a simple two-body case, r1, the distance from the center of the primary to the barycenter is given by:

where:

- a is the distance between the centers of the two bodies;

- m1 and m2 are the masses of the two bodies.

r1 is essentially the semi-major axis of the primary's orbit around the barycenter—and r2 = a − r1 the semi-major axis of the secondary's orbit. Where the barycenter is located within the more massive body, that body will appear to "wobble" rather than following a discernible orbit.

Examples

The following table sets out some examples from the Solar System. Figures are given rounded to three significant figures. The last two columns show R1, the radius of the first (more massive) body, and r1/R1, the ratio of the distance to the barycenter and that radius: a value less than one shows that the barycenter lies inside the first body.

| Larger body |

m1 (mE=1) |

Smaller body |

m2 (mE=1) |

a (km) |

r1 (km) |

R1 (km) |

r1/R1 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Remarks | |||||||

| Earth | 1 | Moon | 0.0123 | 384,000 | 4,670 | 6,380 | 0.732 |

| The Earth has a perceptible "wobble"; see tides. | |||||||

| Pluto | 0.0021 | Charon | 0.000254 (0.121 mPluto) |

19,600 | 2,110 | 1,150 | 1.83 |

| Both bodies have distinct orbits around the barycenter, and as such Pluto and Charon were considered as a double planet by many before the redefinition of planet in August 2006. | |||||||

| Sun | 333,000 | Earth | 1 | 150,000,000 (1 AU) |

449 | 696,000 | 0.000646 |

| The Sun's wobble is barely perceptible. | |||||||

| Sun | 333,000 | Jupiter | 318 (0.000955 mSun) |

778,000,000 (5.20 AU) |

742,000 | 696,000 | 1.07 |

| The Sun orbits a barycenter just above its surface.[1] | |||||||

Inside or outside the Sun?

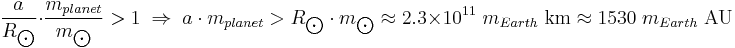

If m1 ≫ m2—which is true for the Sun and any planet—then the ratio r1/R1 approximates to:

Hence, the barycenter of the Sun-planet system will lie outside the Sun only if:

That is, where the planet is heavy and far from the Sun.

If Jupiter had Mercury's orbit (57,900,000 km, 0.387 AU), the Sun-Jupiter barycenter would be only 5,500 km from the center of the Sun (r1/R1 ~ 0.08). But even if the Earth had Eris' orbit (68 AU), the Sun-Earth barycenter would still be within the Sun (just over 30,000 km from the center).

To calculate the actual motion of the Sun, you would need to sum all the influences from all the planets, comets, asteroids, etc. of the Solar System (see n-body problem). If all the planets were aligned on the same side of the Sun, the combined center of mass would lie about 500,000 km above the Sun's surface.

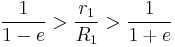

The calculations above are based on the mean distance between the bodies and yield the mean value r1. But all celestial orbits are elliptical, and the distance between the bodies varies between the apses, depending on the eccentricity, e. Hence, the position of the barycenter varies too, and it is possible in some systems for the barycenter to be sometimes inside and sometimes outside the more massive body. This occurs where:

Note that the Sun-Jupiter system, with eJupiter = 0.0484, just fails to qualify: 1.05 ≯ 1.07 > 0.954.

Animations

Images are representative (made by hand), not simulated.

Two bodies of similar mass orbiting a common barycenter. (similar to the 90 Antiope system). |

Two bodies with a difference in mass orbiting a common barycenter external to both bodies, as in the Pluto–Charon system. |

Two bodies with a major difference in mass orbiting a common barycenter internal to one body (similar to the Earth–Moon system). |

Two bodies with an extreme difference in mass orbiting a common barycenter internal to one body (similar to the Sun–Earth system). |

Two bodies with similar mass orbiting a common barycenter, external to both bodies, with elliptic orbits (a common situation for binary stars) |

|||

Relativistic corrections

Within classical mechanics, this definition simplifies calculations and introduces no known problems. In the General Theory of Relativity, problems arise because, while it is possible, within reasonable approximations, to define the barycentre, the associated coordinate system does not fully reflect the inequality of clock rates at different locations. Brumberg explains how to set up barycentric coordinates in General Theory of Relativity.[2]

The coordinate systems involve a world-time, i.e., a global time coordinate that could be set up by telemetry. Individual clocks of similar construction will not agree with this standard, because they are subject to differing gravitational potentials or move at various velocities, so the world-time must be slaved to some ideal clock; that one is assumed to be very far from the whole self-gravitating system. This time standard is called Barycentric Coordinate Time, abbreviated "TCB."

Selected barycentric orbital elements

Barycentric osculating orbital elements for some objects in the Solar System:[3]

| Object |

Semi-major axis (in AU) |

Apoapsis (in AU) |

Orbital period (in years) |

|---|---|---|---|

| C/2006 P1 (McNaught) | 2050 | 4100 | 92600 |

| Comet Hyakutake | 1700 | 3410 | 70000 |

| C/2006 M4 (SWAN) | 1300 | 2600 | 47000 |

| 2006 SQ372 | 799 | 1570 | 22600 |

| 2000 OO67 | 549 | 1078 | 12800 |

| 90377 Sedna | 506 | 937 | 11400 |

| 2007 TG422 | 501 | 967 | 11200 |

For objects at such high eccentricity, the Sun's barycentric coordinates are more stable than heliocentric coordinates.[4]

References

- ^ "What's a Barycenter?". Space Place @ NASA. 2005-09-08. http://spaceplace.nasa.gov/en/kids/barycntr.shtml. Retrieved 2011-01-20.

- ^ Essential Relativistic Celestial Mechanics by Victor A. Brumberg (Adam Hilger, London, 1991) ISBN 0-7503-0062-0.

- ^ Horizons output (2011-01-30). "Barycentric Osculating Orbital Elements for 2007 TG422". http://home.comcast.net/~kpheider/2007TG422Barycenter.txt. Retrieved 2011-01-31. (Select Ephemeris Type:Elements and Center:@0)

- ^ Kaib, Nathan A.; Becker, Andrew C.; Jones, R. Lynne; Puckett, Andrew W.; Bizyaev, Dmitry; Dilday, Benjamin; Frieman, Joshua A.; Oravetz, Daniel J.; Pan, Kaike; Quinn, Thomas; Schneider, Donald P.; Watters, Shannon (2009). "2006 SQ372: A Likely Long-Period Comet from the Inner Oort Cloud". The Astrophysical Journal 695 (1): 268–275. arXiv:0901.1690. Bibcode 2009ApJ...695..268K. doi:10.1088/0004-637X/695/1/268.